Book of Job

The readings are interspersed with my notes, but you can get

a quick list here

Issues

·

The dichotomy between the purported issues at hand—whether man

is capable of altruism—and the actual issue, whether God does justice in this

world

·

Lack of perfect synch between the pose and the poetry, or more

specifically between the framing story, and the debates that take up the middle

section of the text.

o

One author, or multiple authors

·

Construct problems:

o

What happens to the third

friend? He has no conversation

o

Eliyhu

comes out of left field

o

2 sections of God speaking rather than one

Ibn Ezra held that it was a translation from Aramaic.

Tur-Sinai (Bibliography #22) feels that it

What the Rabbis Said

Tzvi Segel (B. #43 I think) has a Mavoh Lamikra with a nice

compilation (and some thoughts) on Rabbinic writings on Job.

The Debate in Baba Batra (14b,

15a - 15b)

indicates that the Rabbis did not have a mesorah as to the authorship of the

book. The Rambam

(Guide to the Perplexed 3:22) follows this up by saying that the book is a

Mashal (check this out to be sure), like the one opinion in Baba Batra. This

opens up a Pandora’s box allowing one to say than any story in the bible is a

fiction. Commenting on the is Moshe

Greenberg in Shaa’arei Talmon (Bibliography #92) Greenberg (I think) cites

a 13th century exegete, Rabbi Zecharya (B. #10), who states that the

book is certainly a Mashal.

References to Job

Ezekiel, dealing with the Issue of Schar and Onesh being

directed at the innocent/guilty, and not their kids, cites as righteous men:

Noah, Dan’el, and Iyov (14:12-14,

and 28:1-3).

Dan’el is pronounced (Kri’) Daniel, although it is spelled without

the Yud. It does not seem likely

that Ezekiya’s contemporary would be so referenced.

Uggaritic texts have been found with a wisdom story about Dan’el, so

this is probably who Ezekiel was referring to.

(The Book of Enoch (Chapter

4?) may also include an Danel reference..) In any event, it seems that Iyov the

person was known as real to Ezekiel and his audience.

A Synergy: Real-“ish”

There exists a possibility that Iyov was a real person, and

around him was constructed a wisdom story.

So Bereishit Rabbah (no reference).

Commentaries

Amos Chacham in Da’at Mikra, especially for philological

(B. #1)

Rav Yoseph Kara (B. #3)

Schwartz (B. #10)

Rashi and Rabbeinu Tam, Shoshana (B. #17)

Rashabm,

Japhet, S (B. #18)

Assignment

Read Chaps 1-2 with Amos Chacham and the Greenberg

article (I think B. #22). Also mentioned Ginsburg

(I think)

Read Meir

Weiss. Bereishot Rabba quotes Reish Lakish that Iyov never was, and then

goes on to explain that it meant the punishments never occurred, but Iyov was a

real person. The author needed a character that the reader would believe would

act the way his protagonist does and stand up to the punishments. (By the way,

the one who warned about the Pandora's box of saying the story and person are

Mashalim is Rav Ibn Caspi). Read Shmuel

Lieberman (B. #36) which is cited by Greenberg.

Focuses on a change to the talmudic text from "Mashal" to "LiMashal"

supporting the idea that a real person (Iyov's) life was used FOR a Mashal.

(Eric: I'm a bit confused here. The way I read Lieberman, Iyyov AND his

life were real, but the reason his life was so pitiful is that he was created

specifically to undergo those challenges do that his REAL life could be used as

a Mashal.)

Rav Zarachya's proofs that Iyov was not real:

- The use of similar language style by different characters

- Yehezkal does not necessarily know who Iyov was

Issue: Iyyov is considered a wisdom book. The moral and message are

universal. Proof: The Tetragrammeton appears in the opening and closing

framing story, but appears only twice in the body of the work. Both times (12:9

and 28:28) the use is idiomatic, and probably a direct quote. 12:9 appears in

Yishayahu.

So why choose a non-Jew as a hero. Perhaps the author wanted to create a

universal work, rather than just a Jewish one. The Bedouin references and

ancient language also give it an air of ancientness, but do not necessarily mean

it was written then, but that the author used the ancient phraseology intentionally.

Justice: Lack of justice. Yehezkel Kaufman (B. 47) (Only to p. 604? Not

sure. Eric.) in chapter on Torat Gemul. Personal vs. Group, referrers to the

two types of Gmul: Group and Individual. Personal Gmul finds its best

representation in Ezekiel 18, and maybe in Jeremiah 31:26 (based on the way it

is understood.) Some scholars wanted to say that Personal Group was only an

issue for individuals, rather than in ancient times, and therefore the book must

be late. However, there is plenty of personal Gmul in the Torah Devarim: Don't

Kill Father/Sons for the sins of Sins/Fathers, although this might be referring

only to human judges, not God. Also found in ancient, even Sumerian texts, so

don't reject the personal Gmul as "modern." Not true. On this See

Weiss (B. #26)

Group vs. Individual Recompense.

Weiss

says there is no distinction, the prophet speaks to whatever problem needs to be

addressed (Eric: Not sure what this means.) Optional Reed: Article by Tzvi

Weinberg (#31).

See Fables and Didactic tales in ANET or Bayamim Harchokim Haheem, S. Shapira

(1) A Dispute over Suicide (Egyptian), (2) Sumerian

Wisdom, Man and hid god, Samarian variation on the Job Motif. (3) "I

will praise the lord of wisdom" (Babylonian Job) (4) Dialog

of Pessimism (like Kohelet), (5) The

Babylonian Theodicy.

Rav Ya'akovson does a summup of all the places where Reward and Punishment is

mentioned in the Tanach. (Olam Hatanach, Nispach A. (Eric: Do Qumran

Sectarian Texts deals with Schar and Onesh, and if so, How?)

Gordis, Book

of God and Man (P31) Wisdom of Job and chapter 5. Gordis also has a good

translation. See also 3

introductions in JPS Job. Language issues on the Prosaic section in JBL #76

Substratum in the Prose of Job. Avi

Hurvitz, The Date of the Prose-Tale of Job Linguistically Reconsidered (HTR 67 (1974) 17-34 )(#74)

Dating the Book

Iyyov: Mentioned again the critics who believe that the book must be later

(person) based on later use of terminology. An example is "Hayu Chorshot"

which is present perfect (or something like that) which is not present in the

Torah and older biblical books. Mentioned reading Greenberg and Horowitz on the

subject. The assumption is that there was a core ancient story, around which the

author wrote his book. The editing of new text onto older text leaves

"stitch lines" which are apparent. On this see Shalom Spiegel (#87

Sefer Yovel to Louis Ginsburg - He also has a famous article on the Akeida). He

points out that 42:11

is actually the natural extension of 2:10

in the original story, as verse 42:10

already has Job restored in double, why do we need the mention of people coming

to comfort him, and giving him a Ksita to regain his wealth. See also Gordis

Special notes #41: The Juncture in the Epilogue.

What's in a Name?

Rambam sees the name (as the whole story) in allegorical terms, and following

after the Gemara

B"B 16a where Iyyov is interchanged with Oyev, or one who has enmity

put upon him. However, one should note that names don't always match their roots

("Zeh

Yenachameinu" should have produced Nachum, not Noah. Shmuel

should have been Shaul. Moshe

is also not a good fit to Mishitihu. However, Yishayahu uses Moshe's name (63:10-12)

as "M'shoch" or pull.

The name Iyyov has actually turned up in ANETs-especially Acadian-from the

second millennium up through close to CE. The Acadian version might be Ayya Abu,

or "Where is Father" or "where is God" which fits the story.

So Albright.

Iyyov might also be from Ov. One who return (either repentance or a

resuscitation/resurrection). Like in an Ov, necromancer, one who brings back the

dead.

Also, the name might match the Edomite king's son Yovav (Genesis

36:33) (Eric: In fact I think Sarna mentions in the Intro to JPS that Eben

Ezra took some pains to convince people that Iyyov and the Edomite Yovav of

Genesis were not one and the same.)

The

LXX (which is rarely useful in Iyyov studies since the translation indicates

that the Greek translators were themselves perplexed by the difficult vocabulary

in Iyyov, sometimes resorting to guessing and sometimes resorting to deleting

whole verses) has an Epilogue that the name means "He will rise again with

those whom God will raise up. This book comes from Utz in Syria on the boarder

between Edom and Arabia. He took a Jewish wife and changes his name to Chanun."

The same Epilogue is also found in the Apocryphal Tzvaot

Iyyov." Both paint the person and setting as historical, not Parable,

and Support the name Yov.

Chapter 1 and 2

Curse and Bless

Blessing and Cursing Job's wife's advice to "Bless God and Die".

The use of the word "Bless" when curse is meant is similar to a

concept called Tikkun Soferim (See Lieberman's Hellenism in Jewish Palestine on

this), but this is not found in any Tikkin Soferim list mentioned by the Rabbis.

HaSatan

See Wiess

on the subject of HaSatan. There are three uses of Satan in biblical

literature. 1) Something

sent to interfere (Like by Bilam). 2) A

prosecuting Attorney (Like Zecharya) (C) A manifestation of God's

destructive side. This third one shows up more in later literature (See how the God

who causes David to sinfully count his people in II Samuel is changed to the

Satan in

the identical story in I Chronicles.) Apparently, the later generations (Eric:

Exilic?) saw the need to separate the destructive from God himself (Eric: to

keep God Kindler and Gentler? Not at the root of all the destruction and

exile??). Sefer

Hayovlim has God changed to Satan in the Akeida story by Avraham. Also note

the Rabbinic statement that the Satan came to Sarah with the story about the

Akeida, with disastrous results. The inner conflict is anthropomorphized into an

outer conflict. This is why some think of this as a later text, but the

following things should be noted: A) The Satan shows up only with the Heh

Hayedia: [Ha]Satan, indicating a work/duty, not a person. B) there is no mention

throughout the book of a test or bet between Satan and God. It's a non Issue.

The bad things that happen are not a test, they are just something that happens.

A Satan doesn't show its ugly face past chapter 2

This brings up the whole issue though of tests. See the Ramban on Iyyov

(Found in Sha'ar Hagmul, at the End of Torat Ha'adam in Kitvei Ramban) which

presents the idea that God doesn't bang on cracked containers; tests are only

given to those who will be successful in order to make them better. (Eric:

What doesn't kill us makes us stronger?")

Vaya'an

Chapter 3 open up with Iyyov Saying and "answering" Vaya'an. Ibn

Ezra points out the possibility that there is missing words from the friends

like "What happened to you, dude?" Much like the Kohen might ask the

Pilgrim of the First Fruits: "What do you have in the basket?"

Rav Yosef Kara says the word always means that a voice is raised: like the

Levi's on Har Eval and Gerizim, and is not necessarily an answer. See also the

Grossman article. (See Pozansky and Greenberg in Encyclopedia Mikra'it companion

on Rav Yosef Kara and other medieval exegetes.)

Read an article by Tzvi Weinberg from “Shnaton Hagot

Bimikra ז"לשת

#31.

Chapter 3

Ramban explains the cursing of nights and days to be

Job’s stating of his astrological worldview, and because he has an awful

horoscope, he is wishing that he had been born on a luckier day.

However, the speech seems quite emotional and passionate, and the cursing

of the day can be understood, like by Jeremiah (who certainly didn’t have a

astrological-based belief system), as lashing out at the start of all his

problems, rather than the source of all his problems.

What he is in fact saying is that he wishes that he were dead.

Breakdown of the Chapter:

1.

3-10: Better not to have been born.

2.

11-19: Death is better

3.

20-23: Turns against God—why does God allow suffering. (Eric:

Notice the switch of “lasuch” a wall of stones which in chapter 1 is used by

the Satan to describe how God unfairly defends Job, Job turns it around here and

says God unfairly shuts him down.)

A Word about David Yellin, "Chokrei Hamikra"

Lonely Job

See article

by ED Greenstein “The Aloneness of Job”, in a book by Mazon (#38).

Notice that in the comparison to Jeremiah

20:14, in the latter Jeremiah references people, e.g. his mother’s womb,

the one who told that a child was born. In Job, the womb is ownerless, and

teller of the birth is unnamed. All

people references are removed except Job himself who is the “owner” of the

Stomach that he emerged from (not his mother!).

Job loses wealth, family, and ultimately disconnects with the people

around him. Even God doesn’t show

up to help out Job until the end, quite different from Jeremiah and Abraham’s

tests. (Eric:

Perhaps the wife piece indicates the withdrawal/loss of wife as well.

And no wife, no future.)

Grammar of “Hora”

Seems to be passive Kal, which has been lost to Hebrew

Grammar. I have no idea what this

means.

Plays on Words

Notice the word “`HD” (v.

6), which seems like it should mean count or include, but sounds like Yitro’s

‘HD which means happiness, from

the root HDH (like Chedvah). In

fact, the proper form for “include” would have been like by Shimon

and Levi’s “blessing” from Ya’akov.

What the author seems to be accomplishing here is what Yellin calls

“Mishna Hora’ah”: teaching two things by playing with one word.

So by redoing the vowels, the word, matches with “Spor” “to

count” in the same verse, and “happiness” “Ranana” in the following

verse. Other examples are

·

Ha’amek

Sheola: Isaiah 7, meaning To

Ask and Hell

·

Tikva: Job 7:6 meaning hope and string.

Another different form of wordplay is where one word

matches a close-by word but is forced to change meaning: Like “Yaft…LiYafet”

Showing Some Concern

Please note that final verse in chapter 3 indicate that Job

was worried about thing before all heck broke loose. Perhaps that coincides with his sacrificing for the sake of

his maybe-sinful children in chapter 1. Maybe

he is trying to tell God (us, the

audience?) that he was not some nose in the air rich guy, but someone who was

always cautions about steering clear from sin.

Chapter 4

Two ways to understand “M” in verse 17.

Can you argue better than God (Mem Yitaron) or “can you be righteous in

front of (or in comparison) to God. The

latter presents Eliphaz’s problem. He

has no idea what Job did wrong. And

since he can’t point to anything specific, he says that everyone has some

flaws. Throughout the speech, Eliphaz wavers between giving Job

consolation, and accusing him of some guilt, justifying God’s actions.

(Eric: I wonder if “viLo techeteh”

in 5:24 indicates “ a day will come when you won’t sin? I.E. like you were

before.) Fullerton

noticed this duality of comfort and attack.

Yair

Hoffman (#62) wrote that the use of equivocal words is intentional, implying

a double meaning. Later, we will

see that Iyov is upset with Eliphaz since he can’t site a specific sin.

Based on this Hoffman points out that the poetic/philosophic middle

section was written by the same author at the same that he redacted the

bracketing prose since they are symbiotic:

·

Without the introductory story, we would have to agree with

Eliphaz that perhaps Job has sinned. Without

the intro telling us that God Himself attests that Job has not sinned, we would

not understand Job’s anger at Eliphaz. Additionally,

there would be no need for the over-

·

exaggerated presentation and testimony to Job’s purity in the

intro, if we didn’t know what was coming in the middle.

(Eric: Sarna says that this dramatization is common in ANET epic

literature, but perhaps he would still agree.)

Eliphaz's First Speech: Chapter 4

Double readings

Continuing with yesterday's discussion of The

Heart of Eliphaz's Claim and Hoffman's assertion of intentional double

meanings. These include: (Notice that Rashi always takes the negative

view of Eliphaz.)

- Hanisa (v.

2):

- Test. So Rashi. I.e. "You failed on the first try."

- Let's try.

- YiSarta (v.

3):

- L'Chazek, L'Oded: (proof-text = "Ashrei HaIsh Asher TiYasrena

Yah") From the word belt, indicates a strong belt or tie.

- "You are punished." So Rashi

- Kislatecha

- "Fool" So Rashi. Ralbag goes with the

"trust/faith" explanation, but turns it negative, like Rashi.

- Trust/Faith. So Ibn Ezra. See the Gemara Baba Matziya 58b

and Tosafot. Yellin explains how "Kesel" relates to both

fool and trust, since thinking biblically is tied to the heart, and CSL

is the fatty stuff that covers the heart, limiting one's ability to

think correctly. See Yishayahu

6:10.

The overall sense is that the author of Job is painting Eliphaz as one who

talks out of both sides of his mouth, remaining noncommittal.

Sanctimoniousness

The author of Iyyov seems to be presenting negatively the view that one can

balance God's checkbook. (Eric: I got that expression from Rav

Lichtenstein who asked about the then head of Shas: It's amazing that a person

that can't balance the books of his own political party can balance the books of

God.)

Modern vs./ Biblical Hebrew

Note: "Rov" (v.

14) means "my many", or "all of my many" rather than the

modern usage "most" One must always be careful to understand the

usage in the day's of the author.

Angel's Vs. Man

The Kal viChomer (If X is true, than Y is certainly true) comparing the non-righteousness

of Angels to the certainly non-rightous humans is not clear cut, based on

the stated problem of one being born of "Chomer", the physical.

The dichotomy between "Ruach" and "Chomer" is not really

presented in Tanach. Perhaps the problem is the tendency of Chomer to

desire sin, but this is not stated.

Ash

Most translate "Ash" (v.

19) as worms, as in the body is eaten by worms. Yellin, based on the

use of this word in 27:18 prefers a house (Eric: did he mean a cacoon)

which is an unstable structure. This wopuld then match the concept of a

weak "Yesod" and "Bayit" in the verse. Arabic is

the source for thus usage.

Chapter 4

The class started with a little backtrack.

We reviewed the difficulty of the Angel/Human

comparison (4:18-19). Rav Josef

Kara supported the idea that humans are inclined to failure because of their

physical makeup.

Chapter 5

Prevention

Small note: Eliphaz seems to be referring to a preventative

punishment in 5:17.

God punishes so that humans will be introspective and self-assessing.

This, however, seems out of scale compared to the severity of punishments

Job received, and Job rejects it.

Kedoshim

Who are these Kedoshim

in 5:1? Amos Chacham explains

it in terms of the angels, as is often seen from liturgy.

But who said that Job was turning prayers towards angels.

Gordis says that Kedoshim can be understood as God.

See Hoshea 12??? Have to look this up!)

Gordis explains that the “M” is not “from” but “except for”,

i.e. “who except for God should you turn to?”

Ekov

'Ekov'

is difficult. Eliphaz is

talking abstractly about what happens to bad people, so why should he include

his own curses into the picture? Notice

that the destruction of bad people is automatic, or comes from God, as an

example in Tehillim 37:9, 10,

13, etc. Gordis

says that it is a declarative use: I declare that they are cursed.

While declarative usually is in Hiphil or Piel, he adduces some Kal uses

as well.

Why do the Evil Prosper (and Why are we so focused on them)?

The focus is usually on why the evil prosper rather than

why are the righteous smitten. This

change of focus is particularly strange here since Job has not been complaining

about the prospering of the wicked, but his own situation: a righteous man who

suffers. Perhaps the answer is that

an Evil person spits in the eye of God, and therefore it seems unacceptable that

God should not respond. See Tehillim

73:11, also Habakuk

1:5-15. (Eric: It seems to

me that the Tehillim proof seems to be concerned that the righteous will be

swayed by the success of the Evil, and turn away from God.)

Amal

The use of Amal in 5:6-7

seems contradictory. In 6 Eliphaz

is saying that Amal (punishment) don’t grow out of the earth, but they are the

result of wicked action. Then he

says in 7 that Man is born for punishments, i.e. it is an inevitable part of his

existence. So which is it?

Possible answers:

- Rav

Josef Kara: Ignores the contradiction and says: True, man leans to sin so

much, he has no escape from punishments.

- Amos

Chacham: Inserts words to create the following meaning: Man is the father of

Amal, and gives birth to it.

- Gordis

and Kahana agree with Chacham that the implication is than man gives birth

to punishments, but they change the Masoretic reading from Yulad to Yoled to

support this reading. (Eric:

who knows what they will redline next!)

- Shadal

says that Eliphaz is quoting from a source he does not agree with, i.e. “I

have heard that some say ‘Man is born to suffering…’ but I say I will

turn to God…” This is also Ibn Ezra’s approach to understanding the contradiction in Kohelet between 3:17

and 9:10

(Eric: I’m not sure I got these verse correct). See Da’at Mikra on

this.

Play on Words

|

Job

|

Other

|

|

וַיֹּשַׁע

מֵחֶרֶב

מִפִּיהֶם

|

וְחֶרֶב

פִּיפִיּוֹת

בְּיָדָם

(Psalms 149)

|

|

וְעֹלָתָה

קָפְצָה

פִּיהָ

|

Look this up!

|

|

הִנֵּה

אַשְׁרֵי

אֱנוֹשׁ

יוֹכִחֶנּוּ

אֱלוֹהַּ;

וּמוּסַר

שַׁדַּי אַל-תִּמְאָס

|

Devarim 12???

|

|

יִמְחַץ,

וְיָדָו

תִּרְפֶּינָה

|

מָחַצְתִּי

וַאֲנִי

אֶרְפָּא

(Devarim 32)

|

|

כִּי

הוּא

יַכְאִיב

וְיֶחְבָּשׁ;

יִמְחַץ,

וְיָדָו

תִּרְפֶּינָה.

|

כִּי

הוּא טָרָף

וְיִרְפָּאֵנוּ;

יַךְ,

וְיַחְבְּשֵׁנוּ (Hoshea 6)

|

6 and 7

See article in Encyclopedia Mikra'it “Mispar” on the

use of numbers in and out of parallels.

Chapter 6

בְּמֹאזְנַיִם

יִשְׂאוּ-יָחַד.

While modern day usage of "Yachad" means together, and there is

certainly an element here of that, the word is usually equated in biblical parallelisms

with all - "Col." e.g. Tehillim

98, 49,

and Job 3.

כַּעְשִׂי is clearly a

back reference to Elphaz' statement: כִּי-לֶאֱוִיל,

יַהֲרָג-כָּעַשׂ

in the previous chapter. Ca'as here, however, means pain and sorrow, not

anger. See Job

17:7 (parallel to "TZar") and Job

10:17 (parallel to "Eidecha" = wounds, so Ibn Ezra) Notice

also Tachanun.

וַאֲסַלְּדָה

is from the root SLD which means to recoil, not like its later liturgical usage:

prayer.

Judging Job

Job's testimony in verse 10 requires us to judge its veracity. Iyov

says he never spoke badly to (about?) God. Is this so? Perhaps

anything less that actually cursing God, which was the Satan's contention, is

considered passable.

Why

Verse 24 contains a key element to understanding Job. He really does

not know what he has done wrong, and really wishes that someone would tell him.

Verse 27 is a play on Mishlei (not sure where) with a change from Rah to

Rei'ah.

Chapter 7

"Not enough time" seems to be the issue in the opening

verses. He doesn't have time to wait while God changes his fate, as

Eliphaz promises that he will.

The Everafter

In verses 7-10 Iyov doubts the future. According to Chazal in BB 16a

Iyov is doubting that there is Tchiyat Ha'Meitim. So Rashi.

Rav Y. Kara however explains the the plain sense simply means that Iyov believed

it will take a long time to come back to life. Amos Chacham says that

there is no reference to resurrection: Job is talking about a second chance at

life that won't be coming.

Moari states that Iyov, like everywhere else in Tanach, is not

referring to the world to come. Tanach is firmly grounded in this world,

and deals with issues of reward and punishment in our lifetimes. See Ibn

Ezra on this (not sure where!)

Isaiah 26:15-19 and Ezekiel 37 are speaking metaphorically. The only

clear reference to the afterlife and resurrection is found in Daniel 12:2.

Bible critics use this as one of the reasons to date the book of Daniel late,

saying that the idea of afterlife and resurrection came only with Hellenism, as

can be seen with the Macabean

story about the mother who lost here 7 sons (verse 7:9). (Eric:

It's amazing how far bible critics will go to take away our religion.

Amazing that we are the founder of the worlds greatest religions, but ours was

the only ancient religion WITHOUT an afterlife principle. It seems to me

that the total absence of anything remotely explicitly stating an afterlife is

proof that the subject was intentionally avoided in written scriptures.

How could an idea so fundamental to the concept of the transcendental soul not

slip in even a little to so much text. It reminds me of what Rav J.B.

Soleveitchik said. Olam Habah is part of Torah Sheb'al Peh.)  Some

point to Job 19:21=29 as a reference to afterlife, and in fact the verse has

been used for Christiological purposes because of its reference to a "Gorali,"

intestinally mistranslated as redeemer. See the Christian

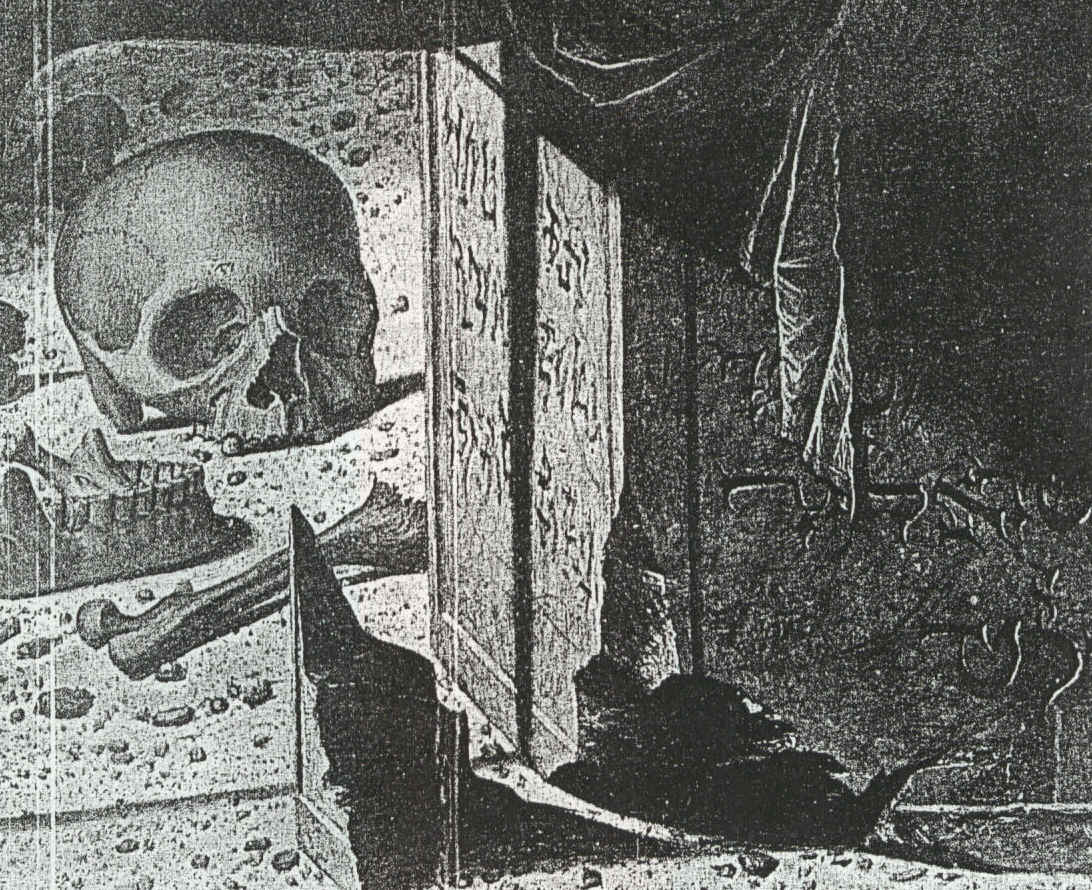

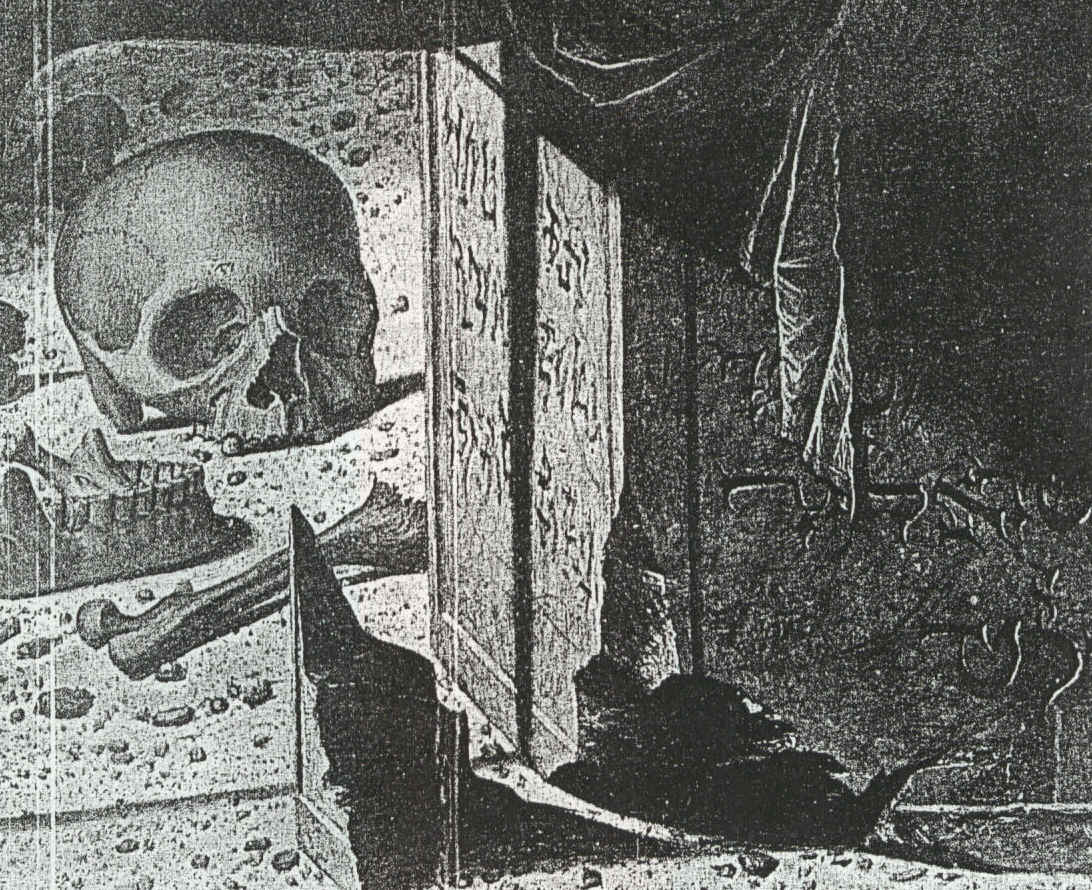

Iyyov painting "The Meditation on the Passion" (at

the Met) with what is said to be Job sitting in chapter 19. The Syriac,

Aramaic, and of course the Vulgate support the afterlife translation.

Actual meaning of Goel: fate, or close relative who buys out debts and takes

care of one in a downtrodden state.

Some

point to Job 19:21=29 as a reference to afterlife, and in fact the verse has

been used for Christiological purposes because of its reference to a "Gorali,"

intestinally mistranslated as redeemer. See the Christian

Iyyov painting "The Meditation on the Passion" (at

the Met) with what is said to be Job sitting in chapter 19. The Syriac,

Aramaic, and of course the Vulgate support the afterlife translation.

Actual meaning of Goel: fate, or close relative who buys out debts and takes

care of one in a downtrodden state.

Chapter 7

Yam - Tanin - Mishmar

Battles vs. Angelic beings. Tehom comes from Tihamat. See

Cassuto's Shirat Ha'Alila. This mythical verbiage disappeared from the

Torah, probably due to the polytheistic overtones. But as time went on the

expressions became cliches, rather than indicating real events and creatures, so

they drifted back into the language. Yishayahu also talks about "Rahav"

but is is metaphoric, similar to Yirmiyahu who talks about the need to

limit the oceans. See also 38:8

Insignificant Man

Compare 8:17 with Tehillim 8. In the former there is an appreciation of

what the mighty hashem does for his insignificant creatures. In Iyyov, the

focus is on: "Leave me alone" and "stop paying attention to

me." In verse 17-20 Iyyov feels that he has become the enemy of the

"State."

Boy, you've got to carry that weight!

Notice the Tikkun in v. 20. "to be a burden upon myself" when

Iyyov really means "a burden on you (God)." (See Eben Ezra who

notes the the verse reads fine as it appears.) The word Masah in verse 20

is being used as "forgive" in relations to sins. The idea is

that God carries the weight of the sins, rather then letting them fall on the

sinner. In a similar vein: Genesis 4:13. Where Kayin

complains: "My punishment is to great to bear." (Notice

that "Avon" probably means "punishment" rather than

"sin.")

Chapter 8

Bildad Gets Tough

Bildad says that Iyyov sinned, but can't specify what that sin is.

However, he is much more direct than Eliphaz, telling Iyyov that he deserves to

suffer. Notice the accusation against his sons in verse 4. Notice

also the conditional "if" starting verse 6. Only if you are

clean will you be absolved. Bildad ends with a warning in verse 22, as

opposed to Eliphaz, who ended more positively.

The Mashal Boundry

The are a few aphorisms or parables starting with verse 11 and ending at

verse 20. The first two 11-13 and 14-15 are clearly (and, in the case of

the first one, explicitly) referring to evil men. The question is: are verses

16-10 a continuation of the evil-guy parable (so Rashi), or are we talking about

the righteous? Gordis prefers the latter since verse 20 sums up with a

reference to both the righteous and the evil, which would require that at least

one of the parables mentions the righteous.

Chapter 9

A Twisted Tzaddik

In verse 2 Job is quoting Eliphaz (4:17),

and the meaning of the word seems to indicate that compared to God, there is

always some flaw that precludes man being considered wholly Tzaddik.

However, this would seem to imply that Job agrees with Eliphaz, which the rest

of the chapter does not support. Rashi in Mishpatim

says that there is a difference between Naki and Tzadik. The former refers

to one that is truly sinless. The latter just means that he won his court

case, not that he is without sin. Iyov is not admitting that he has some

some, but by twisting Eliphaz's words, he states that he can't win the court

case against God. This idea is supported by the rest of the text.

verses 8-10 also either quote Eliphaz

or Amos

or Yishayahu

confirming God's power, but the mood is turned negative by Iyov by his first

citing God's destructive powers in verses 5-7.

Kinuy and Tikkun

Verse 3

in chapter 32 is a listed Kinui, where the author (or scribe) changed

"God" for "Iyov," the conclusion being that the

"friends" conclude that God was wrong. Geiger says that

there were more changes, and shows that the Targumim do it regularly, especially

be removing anthropomorphizations of God. (Geiger, a big Reformist of the early

reform movement in Germany, felt one could play those games with religious law

as well.) Geiger states that verse 11 should be read "ViLo Yioreh" (He

will not see) and "ViLo Yavin" he will not understand. (Eric:

I don't understand why this is necessary. This verse, without emendation,

seems to be an argument against Eliphaz's claim of prophetic authority as his

source, in 4:15-16.

Note the verb "CHLPH." I also don;t understand why it's

necessary to protect God from Insult in this and other verses, when there are so

many verses here that are left in their full chutpadik glory.) So too for

verses 19 ("Yodiyanu"), 24 ("Im Lo Hu"), and

35 ("Hu Imadi") Ezra Melamed (?) wrote an article on

Tikkun Soferim.

Tranlations

Rahav (13) : god of the sea or Egypt. Came to mean egotistical

(?)

Sa'arah (17): Hair ("you analyze me with a fine tooth comb")

or Storm ("you blow me around like in a storm")

Catch 22

Iyyov is presenting a catch 22. If he tries to make God understand that

he has no sins, the very act of speaking out will be considered a sin.

Chutzpa

Rav Yoseph Kara is uncomfortable with chutzpah of verses 22-24, so he says

that Iyyov means the Satan when he says "rasha" and he is

complaining that God allowed the Satan to have his way. This is not the

pshat.

Chapter 10

The chapter flows more relaxed, Iyyov calming down and being much more

supplicant to God, turning inward once fatalistic once again, begging to

understand his sin

Chapter 10

Verse 9 may be ending with a question: "must you return me to the

earth?" Something like: "if you made me like this, don't punish

me for how you made me."

Verse 11: Cahana writes that the pidyon haben is based on this (Eric:

Of have no recollection of what this means!)Verse 14:

Verse 14: "Shmor" is being used negatively here, e.g. "you are

watching my sins," or "holding me accountable for them." This is

on contrast to the use of "shmor" in verse 12.

Verse 15: "Ur'Eh" doesn't mean "to see." Notice the

parallel to "Savah." Instead, the root is RVH, or to be

satisfied, like "Orech yamim asbi'ehu VER'EHU biyshuati.". See

Rashi on the word "Titra'u" by Ya'akov and the famine.

Verse 15-16 indicate a cat and mouse game against Iyyov. Compare to

Yishayahu 5:29.

Verse 21-22: According to Yellin, the words "Lo Ashuv"

should be at the end of the sentence. ("From then land of darkness I will

not return," rather than "I will not return to the land of

darkness.") This is sometimes done for poetic reasons, and the

Ta'amim will prefer the poetry over the correct meaning, such as "In the

beginning God created / the heavens and the earth" really should be

"In the beginning / God created the heavens and the earth."

Verse 22: [Eric: I'll write this word for word from my notes since I do

not remeber what is means!] "Eipha" - Darkness and light:

"IkAr vi'IkUr, so "Ohr." (?????)

Chapter 11

Verses 5-6: Tzophar is saying "Iyyov, you can't understand God"

just as in chapter 28 when Iyyov says this himself, as does God in the

end. The difference is that Tzophar is still accusing him of a sin, just

that he can't understand how the sin matches the punishment. The real

upshot of the book, as shown from the opening two chapters of narrative, is that

Iyyov did not commit a sin! Tzophar can not admit that the truly innocent

ever suffer.

Verse 3: machlim = lig'or. No one castigated you when you spoke inappropriately

(mockingly).

Verse 15: MiMum = B'li Mum (Eric: See Rashi)

Verse 17: Chaled = Your Days. You will get a new life.

Verse 17: Ti'Uphe = the darness will become like the morning. All times

of the day are here: Ti'Uphe (night), Tzohorayim (afternoon), and Boker

(Morning).

Notice Tzophar ends on a negative

Chapter 12

Verse 6: Might makes right.

Verse 9: Notice the unusual usage of God's existential name. This was

probably used since the whole phrase was a common idiom.

Compare the end of the speech in this chapter to Tehillim 107, especially

verse 40-43.

Chapter 13

Here we get a peek into Iyyov's personality. Ityyov hates liars, and

says God hates liars. Here for the first time we sense that he believes on

God (and perhaps his justice). See verses 3-13.

Chapter 12

An Error?

Is it Masgi (to raise up), or Mishgi (to cause to err)? The LXX has the

latter. See Rashi. See medrash Tanchuma Parashat Vayikra Siman 18,

which seems to have a different nusach. Aslo see the Minchat Shai, who

deals with the issue.

Chapter 13

Taking a Risk

The phrase "Naphshi biKapi" generally means to take a risk, as can

be seen by Tiphtach (Shoftim 12:3), Yonatan's reference to David (I Samuel

19:5), and Shaul's necromancer-ess (?) (I Shmuel 28:21). In Iyyov,

this meaning would cause a contradiction: In verse13 and 15 he's going to take a

chance, but in 14 the "Al Ma" which agrees witht he first part of the

verse ("why should I stuff my mouth closed") seems to say "that

there's no use in taking a chance." Gordis sees it as a quote (???)

(Eric: I don;t see the probleem, since the copulative vav can be seen as

"BUT", and therefore disconnected from the Al Mah.

Verse 15 has a "Lo" (Not) and "Loe" to him, Kri/Ktiv.

Many times, both make sence, and perhaps that is the intention. Remeber

that since the "vav" is a Amot Hakriya, there's really no difference

orthographically, even though the mean is quite different. Apparently

Gordis wrote a whole book on this. See Mishna Sota 5:5 and the Gamara on

this.

14:22 - Chazal understand this as the pain after death.

14:10 expressed death backwards. First death and then

weakness.

Chapter 28

In chapter 28, Iyyov recognizes that God's wisdom is beyond man's ability

tocomprehed. If this is so, why does God show up at the end of the book to

restate this? Gordis says that in the first edition of the book, chapter

28 was the last chapter, but the author decided on a new version where God gets

the last word. Yishayahu Liebowitz explain differently. He says that Iyyov

understands that he can't understand, but he does not like it. He doesn't

think it's fair that he can't understand the world around him. He draws a

comparison between Iyyov and Avraham (which satisfies the Ishmael

connections in the names of the characters) where the ultimate lesson is one of

complete submission, and the best way to serve Gid is out of a total loss (Eric:

I'm probably getting this wrong, so please see the article--Avraham and Iyyov--

inside.)

Chapter 28

Verse 11: "Mib'chi" from the Uggaritic. See Da'at Mikra

footnote 45.

Chapter 29

Iyyov wants to turn back the clock. (Eric: I thisk this chapter is

critical since it gives us crucial boa graphical information that helps us

understand the 3 friends' words. Iyyov was a judge, highly respected, and

perhaps senior in his city-state. See verse 7 and on.

Verse 3. Notice the word "Hilo," which might have become

"Halo," the ring of light on the saints' heads.

Verse 4: "Sod" = Company. See Shimon and Levi's "beracha."

Chapter 33

Elihu

The point that he is trying to make is that pains come to purify a man, and

to make him better. The visions at night come to help one reflect and

correct.

Chapters 38 - 42: God and Iyyov

Whay is there the double conversation, why does God talk twice? The

first time Iyyov says he'll shut up, but the second time Iyyov gives in.

Maori thinks the fact that God shows up at all is enough for Iyyov. See

Tehillim 73:17. (??)

Some

point to Job 19:21=29 as a reference to afterlife, and in fact the verse has

been used for Christiological purposes because of its reference to a "Gorali,"

intestinally mistranslated as redeemer. See the Christian

Iyyov painting "The Meditation on the Passion" (at

the Met) with what is said to be Job sitting in chapter 19. The Syriac,

Aramaic, and of course the Vulgate support the afterlife translation.

Actual meaning of Goel: fate, or close relative who buys out debts and takes

care of one in a downtrodden state.

Some

point to Job 19:21=29 as a reference to afterlife, and in fact the verse has

been used for Christiological purposes because of its reference to a "Gorali,"

intestinally mistranslated as redeemer. See the Christian

Iyyov painting "The Meditation on the Passion" (at

the Met) with what is said to be Job sitting in chapter 19. The Syriac,

Aramaic, and of course the Vulgate support the afterlife translation.

Actual meaning of Goel: fate, or close relative who buys out debts and takes

care of one in a downtrodden state.